A year ago, with the world reeling from the murder of George Floyd, the music industry pressed pause for 24 hours for Blackout Tuesday. What followed was the promise of action against inequality and racism throughout the business, and the members of the Black Music Coalition have been leading the charge. Music Week meets Char Grant, Afryea Henry-Fontaine, Sheryl Nwosu and Komali Scott-Jones to tell the story of the BMC’s first 12 months, find out what has happened so far and hear why they won’t stop fighting for change…

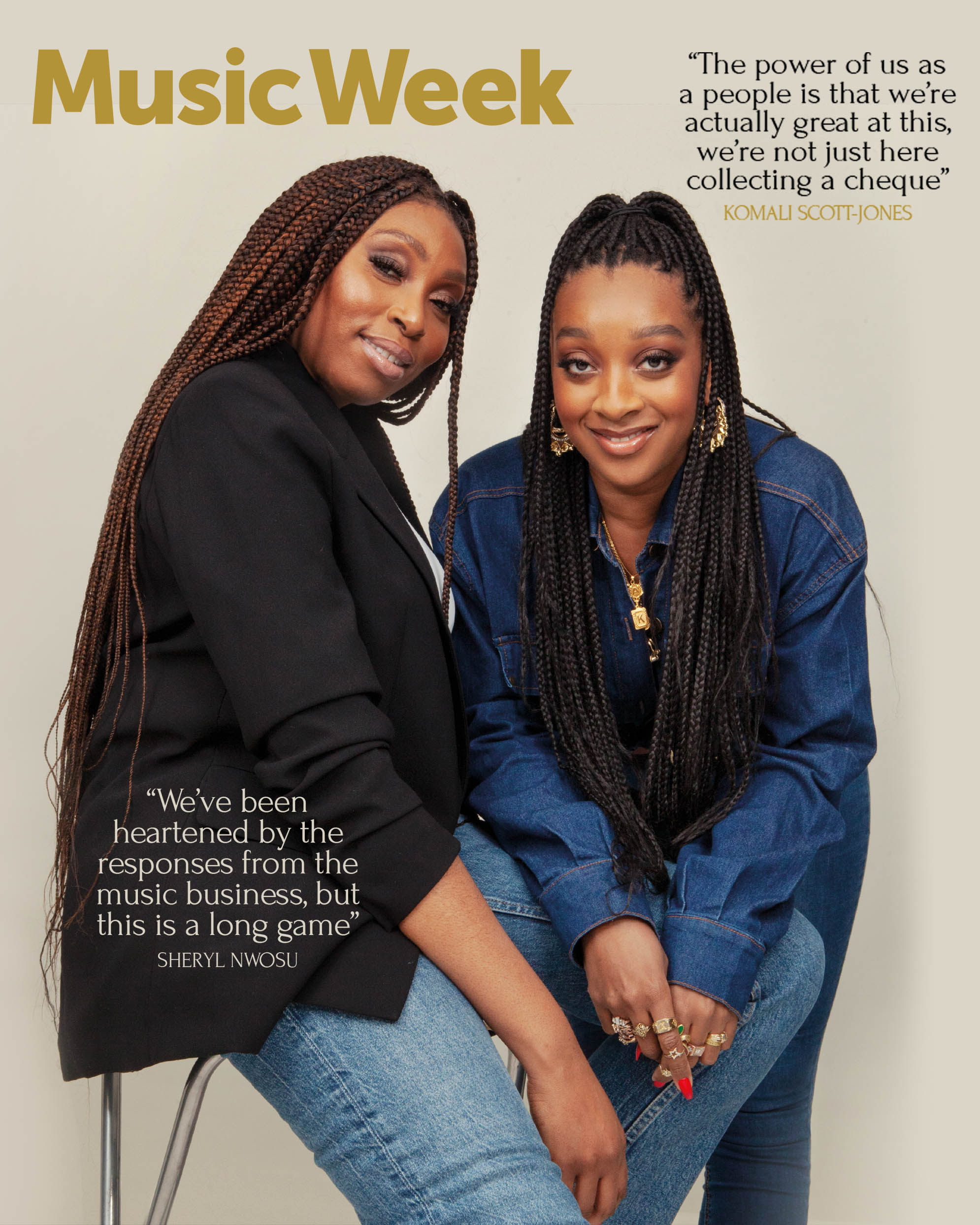

WORDS: Natty Kasambala PHOTOS: Kuka K

This month marks a year since the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed 46-year-old man who died after a police officer knelt on his neck for over nine minutes in an arrest made over a suspected counterfeit $20 note.

“Personally, I was so traumatised… It just broke me,” admits Afryea Henry-Fontaine, director of marketing at Motown Records and co-founder of the Black Music Coalition, which formed in the wake of Floyd’s murder, as Black Lives Matter protests swept around the world.

The former EMI executive remembers waking up in tears and immediately emailing her head of HR and then label president, asking what their plans were to help. Elsewhere, Char Grant, who was working in A&R at BMG at the time, was feeling similarly distraught.

“I was on a call on the Monday morning with my team at the time,” says Grant, who joined 0207 Def Jam in December. “They were talking about a Piers Morgan interview and a few other things and I actually felt sick, I was so upset. I couldn’t even put my camera on, I felt so unsupported. I didn’t even want to be visible.”

The Black Music Coalition was founded by Henry-Fontaine and Grant, together with Komali Scott-Jones, A&R manager at Parlophone, and barrister Sheryl Nwosu, who has been a close friend of Grant’s for 25 years. As a lawyer working outside the music industry, Nwosu was drafted in initially to provide assistance, and quickly became a permanent fixture.

The BMC is dedicated to eradicating racial injustice and establishing equality for Black music execs, artists and their communities. Beyond the exec committee is a sprawling network of Black music executives from all areas, including Atlantic’s Austin Daboh, 0207 Def Jam’s Alec and Alex Boateng, Columbia’s Taponeswa Mavunga, Metropolis’ Whitney Boateng and many more. The collective was established to act in the best interests of its network and hold industry leaders to account in making meaningful and effective changes.

“The bar is very low in terms of how Black people are treated around the world,” Nwosu begins, as we sit down to a long Zoom session with all four members of the exec committee. “We know that on a micro scale, we know that on a macro scale.”

Over the last few decades, there have been many heartbreaking cases like George Floyd’s: those of strangers who become more well-known in death than they were in life. Names that turn into symbols of injustice and violence and rightful rage, names that we hold onto tight and try (but often fail) to preserve their humanity, amidst others’ attempts to erase it entirely.

Floyd’s death was gut-wrenching and cruel, and the world responded with protests and hashtags, heated discourse and trauma, hopelessness and a new-found sense of urgency. But for whatever reason, there was something that tipped the scale that little bit further. Perhaps it was our position in the throes of a pandemic, maybe it was the killings of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery that preceded it, or it could be that it was just the straw that broke the camel’s back.

But how exactly do we get from there to dissecting the nuances of racism and prejudice within the UK music industry? Perhaps the hand-made signs at the Black Lives Matter protests in London summed it up best by stating simply, ‘The UK is not innocent’. This, then, was the moment for the music industry to speak up.

“We’ve seen these stories play out in our own lives, in our workplaces and to us personally as victims of the system, right?” says Komali Scott-Jones. “And then it gets to a point where these videos are shared and constantly on replay in our minds. We’re all in lockdown, a global pandemic, none of us have lived like this before – inside for however long. There’s this added pressure too, you’re working harder than ever, Zoom calls until whatever o’clock at night...”

Scott-Jones continues, the memory still fresh in her mind.

“You see that [Floyd] video,” she says. “And you know how it goes, people will pretend it didn’t happen or say it was OK that it did. But there are a lot of firsts happening right now, and that isn’t going to run anymore. We cannot allow everyone to do an, ‘Isn’t it sad’ at the coffee machine and move on. Nah, we’re not at that coffee machine, we’re at home. And we can and will talk about it... It exacerbated the issue of us having to endure this pain that’s inflicted on us that our white counterparts don’t have to. They don’t even understand what we go through on a day-to-day basis as Black people – as Black women.”

The harsh reality of Black people everywhere who feel a deep connection to cases like George Floyd’s is that they are left to nurse their raw nerve endings alone.

“That spectacle, as it was, affected Black people in a specific way,” says Nwosu. “It was like, we’ve only got each other, you know?”

That realisation led to the communing of a number of Black execs, who had met virtually just a few week earlier on the separate issue of connecting more in lockdown. A WhatsApp group was formed, and a few from the chat decided to do something bigger. Blackout Tuesday had been announced by US movement The Show Must Be Paused – organised by Atlantic Records execs Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang – and felt like an appropriate opportunity.

“All of us had decided we were taking part whether work was on board or not,” Henry-Fontaine explains. “And, as we know, so many companies came on board and supported their Black staff by taking the day. We met that day and I think it was a three-hour Zoom. We didn’t have an agenda per se, it was more come and just be.”

That meeting sparked a reviving bond between a community that had previously existed in smaller social groups.

“I don’t think people were purposely separate before, but there was definitely this big realisation of, ‘No-one feels the way [we] feel about this,’” Nwosu recalls.

Henry-Fontaine says that their first action point was an open letter: “We had to come together and utilise our impact and the effect we can have in our buildings and beyond, to call for change.”

Blackout Tuesday and the outpouring of Black squares across social media granted the BMC a foothold on an otherwise steep and slippery rock face.

“Those squares were definitely an expression of something, but the big question was what?” Nwosu says. “And it made us realise, if we allow people to just post them and go back to work, we’re part of the issue,” Grant chimes in. “We couldn’t do that. We had to find a way to communicate that.”

On June 9, the BMC sent its open letter to chairmen, presidents and CEOs across the industry, predominantly at the major labels, publishers, promoters and DSPs.

“And then it just became this train that I don’t think has ever had brakes,” laughs Henry-Fontaine. “The BMC became this central voice that Black executives know will speak in their interest.”

The open letter laid out an extensive case for the pervasiveness of racism and how it permeates every aspect of our lives including work and why it is no longer – and never has been – OK for the music industry to turn a blind eye, especially while profiting from Black culture. It drew out a list of calls to action addressing five areas: unconscious bias training, career development, internal task forces, financial investment and a shift from the term ‘urban’ to ‘Black music’.

“Sometimes, people hear the word ‘system’ and feel like it’s this intangible manifestation, but what we know, as a whole, is that the system that we’re talking about is the way we’re treated individually,” Nwosu says. “So the word is not intangible to us. It’s not abstract.”

The BMC’s first agenda points were stepping stones to help redress systemic imbalances. The response to the open letter was heartening in both sentiment and sheer breadth. Sony, Warner and Universal each committed funds to anti-racism initiatives on an international scale.

“From a major label perspective I think the intention is there and it’s strong and it’s being backed,” says Henry-Fontaine.

Unconscious bias courses quickly slotted into diaries and social justice task forces came to the fore, from Sony Music’s HUE (Help Unite Everyone) led by recent Music Week Rising Star Bre McDermott-King, to UMG’s Task Force For Meaningful Change, which revealed its UK manifesto last month. Diversity appointments have also been made in the form of Natasha Mann at Universal UK and Charlotte Edgeworth at Sony Music UK, which also worked with consultant Sereena Abbassi. Warner’s head of diversity & inclusion, Nina Bhagwat, was appointed in March 2019. In April, Sony announced the latest beneficiaries for its Social Justice Fund, including Small Green Shoots and Pirate Studios.

On the subject of the word ‘urban’ – which the industry has largely moved away from – Henry-Fontaine acknowledges the controversy around the term from a global perspective. Republic Records was one of the first to ban it, but some questioned the decision, arguing that in fact it allowed for more accurate distinctions between different areas of music that encompassed multiple genres. Urban in that context demarcated entire label departments and radio networks, even if it still had an enemy in Tyler, The Creator, who slammed the Grammys’ urban category (which the event subsequently dropped).

“To see so many companies and publications now championing [Black culture] by not using the term ‘urban’, and using the term ‘Black music’ or referring to the genre specifically has been a really positive step,” says Henry-Fontaine. “Ultimately, this is about eradicating barriers that prevent executives and artists from reaching their full potential, and that term caused a lot of barriers here in the UK.”

Throughout the last 12 months, the BMC has been meeting with leaders, stakeholders and other key players to steer on courses of action, as well as advocating for those who still felt uncomfortable broaching certain subjects within less diverse workspaces. A separate committee now exists to address the specific needs of the independent sector, headed up by Good Energy PR’s Jess Kangalee (see p32). The team also produced a resource pack for interested parties, with the help of intern Yasmine Dankwah.

“We realised that there were loads of ways that we could help the companies we’re holding to task engage with the right people and organisations that can add value,” Grant explains. “It’s not one-size-fits-all, but it’s an incredible resource that companies pay to access, which helps fund our existence.”

Beyond Black music execs, there is also the matter of Black artists within the industry.

“Our Black artists are facing different issues to their white counterparts,” acknowledges Scott-Jones. “[Black] genres are highly inflated with young artists, typically from working-class backgrounds, being offered large advances off the back of the success of a track in a short time period. Not all of them have time to be connected with a solid team, from management to legal, meaning they could be accepting less favourable deals.”

A BMG review released in December illuminated “significant differences” in royalty rates given to Black artists and their non-Black contemporaries, with discrepancies in at least four of the 33 labels BMG has acquired since 2008.

Beyond that, even when artists are signed, the disparities can get worse, due to perceptions of the limits of certain genres, measurements of success or just a disconnect on an interpersonal level.

“There’s an imbalance of pressure placed on them to be [immediately] commercially successful compared to their white counterparts before they’re deemed as an act that ‘isn’t working,’” says Scott-Jones. “There are also disparities in budget sizes around campaigns. It’s a high-pressure environment for artists who are typically also dealing with other obstacles without a support system around them. It has a negative, sometimes detrimental, effect on their mental health.”

And to take it full circle, those attitudes towards Black artists shape the careers of Black execs, too.

“The lack of artist development contributes directly to the lack of executive development,” says Grant. “Think about the culture of bringing young executive talent in to look like the people [labels] want to sign. Things are signed off numbers or social heat, or whatever else that isn’t to do with artistic integrity, the music or the five-year plan. It’s just, ‘It’s a song, it’s working, let’s go.’”

If this short-term focus persists, the careers of those building the campaigns could stall, too.

“At any label building you go into, the top executive talent are the people that have done the journey,” Grant continues. “They’ve stood in the gig with two people, but they’ve also done the arena tour, they know what success looks like. We need to continue developing new artists who we want to take the long journey with, or signing from different perspectives. If that happens, people will be able to grow naturally.”

Additionally, Scott-Jones says, Black executives can end up consumed by dealing with the extra duties that come with working with a roster of artists dealing with the aforementioned hurdles.

“This can be seen with marketing managers or A&Rs having to deal with problems that fall outside their remit, like trying to offer help around financial or legal issues,” she says.

The problem in such cases is two-fold: Black execs are automatically boxed into working predominantly Black rosters, and labels themselves are not equipped to support the distinct struggles of Black artists and thus rely too heavily on that presumed expertise. It’s a pattern that can not only end up limiting the scope and variety of the careers of Black execs, but also risks overwhelming them when infrastructure falls short.

“We urge the wider industry to take note of this and ensure the welfare of these artists and the execs that support them,” says Scott-Jones. “Long before it negatively affects their roster, staff or bottom line.”

Black music and culture are a cultural force in the UK. Amidst a global pandemic and in the wake of unignorable violence, the contribution of Black artists to the overall entertainment ecosystem has become undeniable. Now, issues of race are no longer marginal – because Black culture is mainstream.

“We’ve never been niche, we know that, but we have been explained away [before],” says Henry-Fontaine. “Now, we’re everywhere. And you cannot ignore the community that culture is birthed from any longer.”

Black American culture has long occupied a place in the UK industry and charts. Titans such as Drake, Kendrick Lamar and Kanye West could dominate weekly chart sales at a moment’s notice. And though British genres such as grime, jungle and garage always thrived in the underground, mainstream national recognition was harder to come by, making it easier for music companies to ignore the context that surrounds the music.

We have recently seen the rise of genres such as drill and rap in the UK. Dave, Stormzy, J Hus, Headie One, Nines and Slowthai have all had No.1 albums, while projects from M Huncho, Fredo and D-Block Europe have racked up big numbers. Newcomers and veterans alike are making their mark on the charts: this year, Central Cee and Ghetts narrowly missed No.1 finishes for Wild West (34,962 sales, OCC) and Conflict Of Interest (15,140) respectively.

And though, in an ideal world, change would be founded on compassion alone, if numbers are what it takes to make a case, Black culture is as lucrative as it’s ever been.

Scott-Jones says the first stirrings of this new wave hit in 2015, with the likes of Yxng Bane, Kojo Funds, Abracadabra and MoStack emerging from within the Afroswing genre.

“It felt really exciting and fresh and was probably the newest genre that had emerged from the UK since grime that was intrinsically ours,” she says. “Things were moving, people getting signed, you felt a real shift.”

But Scott-Jones says that surge to sign such artists came with another realisation: “Shit, we don’t have an A&R who looks like that, or who can go to Broadwater Farm Estate and speak to Tion Wayne or OFB.”

With that came a new generation of young, talented Black executives. But can this change be viewed as permanent, or is it just a fad? There’s a consensus among the BMC that, for the most part, people thought it would only last a few years.

“I definitely picked up that vibe,” says Grant, who remembers in her first six months as an A&R, after years managing artists at Modest, being head-hunted by two to three other major labels who were scrambling to diversify their teams. “I struggled to understand, ‘Why are these people offering me these jobs? I am not there, I am not ready...’ But I realise now that it was them collecting the Black people, they just needed anyone.”

Here, we’ve struck on one of the long-term wrongs the BMC is seeking to right: the tokenisation of all Black members of staff to service and translate the Black experience for all. It’s a pattern that leaves people feeling pigeonholed and isolated time and again. In the dash to acquire Black talent as quickly as possible, companies have often failed to provide an adequate framework around these new hires to equip them with the tools to progress, especially when they are some of the first people who look like them to occupy a space.

“You just get thrown into the deep end,” Scott-Jones says. “Not to take away from how talented we are, but speaking for myself, no-one’s taught me that. You are often needed as a Black female voice and that can be a big part of why you get the job. The fact that you’re actually good at it is almost a secondary thing in some cases. But the power of us as a people is that we are actually great at this shit, we’re not just here collecting a cheque.”

According to the most recent UK Music Diversity Report, BAME communities make up 42.1% of apprentices/interns and 34.6% of entry-level roles in the industry, 22.6% of mid-level positions and 19.9% of senior roles. This data groups all ‘minority ethnic’ backgrounds together, rather than just Black executives. And although each figure represents an increase, those numbers show that while Black people are invited into industry environments, there is a significant drop-off at the stage where execs start to gain more control and influence, perhaps due to either lack of career mobility or staff retention.

One of the BMC’s proudest achievements to date is a programme launched to rectify some of those inequalities. It has collaborated with PRS Foundation for Power Up, an initiative formed to address anti-Black racism in the industry alongside YouTube Music and Beggars Group. The scheme will support 40 Black music creators and professionals (20 of each) and assist them with the resources they need to succeed.

“Everyone talks about the financial side of it,” Nwosu laughs, “but actually the bit that makes me most excited is the support and the connectivity to others in the industry who can support people’s goals. Because this is what we’ve been talking about, right? Not just being brought into the industry on a one-dimensional tip – for this artist, or because you’re Black, or you know about certain beats or whatever.”

The participants of the Power Up programme will be at crucial career stages and will gain access to grants of up to £15,000, plus mentoring infrastructure, partner support and marketing assistance.

“Let’s get people in here and let’s make them all-rounders, let’s give them the support that they need to have a real, successful, tangible ride in this industry,” says Nwosu. “I feel like that’s exactly what Power Up is going to be able to do.”

The wider initiative also has plans to work in alliance with the Black Music Coalition to empower Black talent and mould policies to improve representation and wellbeing.

“The reason why I relish [the Power Up programme] is because it’s action – because we’re done with lip service,” Nwosu says, shaking her head in a way that shows she truly means it. “We want to see what you actually put into action, aside from the bare minimum. If you go back to that open letter, those calls to action are bare minimums, that should have been done by now.”

Twelve months on from the incident that led to its genesis, the BMC is plotting for the year ahead and beyond. One of the top priorities is legacy.

“We want to balance our direct action to improve the lives of the Black music community with a celebration of what has been accomplished so far, against all odds…” Scott-Jones explains.

“[We want to celebrate everything] from the beginning of Black music, charting, documenting, coffee-booking, conferencing – all of that!” Grant adds.

Ultimately, the empowerment that the events of the last year have given to Black execs to come together and harness their collective strength through vessels such as the Black Music Coalition is no small feat.

“There’s an unreserved [will to] connect, to celebrate, to be part of what’s happening and that’s visible too,” says Henry-Fontaine. “It’s a statement of intent from the Black community.”

And maintaining that visibility as a vocal and unflinching entity that advocates for progress and asks the hard questions is already proving invaluable. The BMC also plans to focus on strengthening the community of its members to create meaningful bonds and a support system for those at all levels in the industry, especially once ‘normal life’ resumes.

“Overall, we’ve been heartened by the responses of music business organisations,” says Nwosu. “We’ve been so pleased to see the task forces that have come up at various labels and companies. It is obviously a step in the right direction, but we’re aware that this is a long game. In some meetings we have, we’re frustrated by things not moving ahead quickly, then we have to recognise our own mere mortal strength, but people have been moving forward and that has been good to see.”

Even though there’s been an immense shift in the way the industry tackles these conversations, so much is still unknown. The BMC ignited four months into a pandemic, with so much of this incredibly complex discourse taking place remotely. In that time, employees have come and gone, some have never met, labels have been started, offices have remained desolate. Our social interactions have been drastically reduced.

“We haven’t experienced [as many] new situations that will challenge this new awareness,” Grant says. “There’s a lot of good work and a lot of good intentions, but I think getting back into the workplaces and seeing the effects of all of this will hopefully uncover even more.”

So, how much do they think the industry has changed in the last year?

Scott-Jones is measured in her response.

“I don’t think the industry is inclusive yet, I think we’re right at the start of people even acknowledging that this is the case,” she says. “The next step is not just how many Black people work for you, but at what level? Will they still be there in a few years? What does senior leadership look like and how far up the company does that go? And in which departments? Is it just marketing and A&R? And what is their day-to-day experience like?”

Henry-Fontaine jumps in: “And are they being paid equally to their white counterparts? That’s the next one.”

Nwosu, who is equal parts enthused and sceptical about the industry, shrugs and says, “We’ll see, innit…”

And that could have been this story’s headline. As much as we can unpick and rearrange these systems on paper, some of the more real and tangible results will only appear in practice – online dialogue, new hires and big cheques alone cannot inspire a paradigm shift. The hashtags won’t delete the preconceptions or the ‘accidental’ slurs or nicknames brushed under the carpet, or any of the other off-the-record ‘yikes’ moments shared during our call, that are either too specific or too offensive to mention.

“Right now we’re at a safe distance,” Scott-Jones notes. “This is all the easy stuff. But when we’re back in the office, is it going to feel different?”

“Hires, career progression and pay equality are essential, but we also have to look at the environment, because it’s all well and good Black people being in positions, but if everyone around them doesn’t feel like this is the necessary change we need to improve our industry, then we’re still going to come up against problems,” Henry-Fontaine predicts.

So be it task forces, overdue promotions, pay-gap reports, mentorship schemes, adequate mental health infrastructures for staff and artists, diverse and representative signings or just rigorous individual interrogation, it’s clear that the next 12 months and every month after will be crucial in determining whether the awakening in lockdown a year ago was genuine.

For now, the image of five Black women sitting together on a two-and-a-half hour call at night discussing anti-racism work is an all too familiar one. So often the task of solving societal ills is designated to those who fall victim to them by default, while others remain ignorant, wilfully or otherwise. And it’s one of the reasons why one of Nwosu’s most used phrases around this discussion is, “open your purse.” In the event that a group of those individuals find themselves both willing and capable to do the work of educating the masses, that labour should be adequately compensated. Otherwise, what differentiates it from any other form of exploitation?

For that reason, Henry-Fontaine mentions a potential paid membership scheme for the BMC on the horizon, and Nwosu circles back to the resource pack.

“It’s one of the ways we have been keeping ourselves in existence,” she says. “Because this work is long and laborious and it ain’t free.”

Up until very recently when the team received some seed funding and support from the Arts Council, the BMC was being run on a predominantly volunteer basis with all funding coming directly from the pockets of its own committee members.

“As a unit, we understand our value, but it’s predominantly been free, let’s keep it real!” Henry-Fontaine says as we wrap up our call. “And we’re not doing this for payment, we’ve picked up the baton from the leaders that came before us, we’re now in a completely different place where the industry is concerned and we need to do this work. It’s not a martyr thing. I just don’t want anybody to have the same experiences that I or other Black people have had in the industry – to put it simply, that’s long.”

The group breaks into chuckles that show a shared understanding, and before we say goodbye, Henry-Fontaine sits up slightly to deliver one final message: “So let’s do it, let’s make a change!”