Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to get through this thing called death.

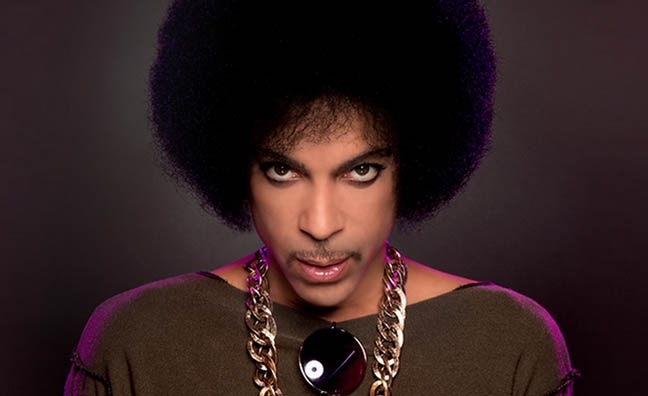

Lord knows, there’s been enough of it this year. But even in these times when you turn on the telly and every other story is telling you somebody died, the passing of Prince Rogers Nelson hits hard.

Because while Prince was a songwriting genius and an amazing all-round musician – on reflection, almost certainly the most talented one of his generation – he was much more than that. In his songs, his vision, his image and the way he did business, Prince didn’t so much break the mould as paint it purple, smash it to smithereens and put it back together in an entirely new shape that somehow still worked perfectly.

So it seems almost unthinkable that he should have left us, particularly in such prosaic circumstances as to be found collapsed from a suspected prescription drug overdose in a lift at the Paisley Park home/studio complex that had become almost as mythical as the man himself. If he had to go, surely it should have been by being recalled to the mother ship or by floating off to some peach-hued Valhalla, accompanied by choirs of Valkyries.

But no, there we were on a Thursday evening, suddenly living in a world without Prince. Your correspondent was in Los Angeles at the time, where the response was immediate: suddenly, every car radio, every shop started blaring out The Hits.

And what hits they were. Many have made the point that he could have constructed one of the greatest albums of all time around the songs he gave to other people – Nothing Compares 2 U, Manic Monday, I Feel For You, The Glamorous Life, Sugar Walls. But the songs he kept for himself were even better.

Born in Minneapolis to musically-inclined parents, his recording career may have started in relatively unremarkable form with 1978’s For You and not truly hit its stride until 1982’s fifth album 1999, but right from the start he set out his stall. He made music that genre-hopped effortlessly in a way that hadn’t even been invented yet. He wrote lyrics that were filthy, but somehow never crass. And his every note contained an effervescent, impish sense that something magical was either already happening or would come along very soon. His name was Prince and he was funky. But he was so much more than that.

During his 1980s imperial phase, it actually seemed like Prince could do no wrong. 1984’s Purple Rain was his real UK breakthrough, aided by the ridiculously brilliant/brilliantly ridiculous film of the same name, and a sound that was at once familiar – part Hendrix, part James Brown – and yet utterly otherworldly. Your correspondent remembers spending much of the teenage summer of ’84 trying to work out how When Doves Cry could sound so weird – discordant guitar, wonky beat, impenetrable lyrics – and yet sound so perfect on the radio. The album went on to sell 22 million copies worldwide, so someone figured it out.

Many artists would have worried about how to follow up such a record. Prince, of course, knew exactly what to do. He released the sublime slice of psychedelia that is Around The World In A Day with minimum fuss and maximum artifice. And even his ‘weird’ album contained Raspberry Beret, one of the most perfect pop songs ever recorded.

He refined that sound on 1986’s Parade, the soundtrack to Prince’s second film, the rather less ridiculously brilliant, but still brilliantly ridiculous Under The Cherry Moon, which gave the world Kiss – a song so powerful it briefly turned indie band Age Of Chance into pop stars and revived Tom Jones’ career – and Sometimes It Snows In April, the melancholy ballad so many turned to when news of his untimely death spread. The following late April day, it did indeed snow across much of the UK, proof that Prince was every bit as maverick and successful a weatherman as he was a musician.

He followed that with the mind-blowing minimalism of 1987’s Sign O’ The Times, a record that combined the hard-hitting political docu-drama of the title track with the out-there pop of If I Was Your Girlfriend and an album so unstoppable that it even managed to reinvent Sheena Easton on U Got The Look.

1988’s porno-goes-gospel epic Lovesexy – unfathomably his first UK No.1 – may have been the last installment in his run of absolute perfection but Prince’s output was by now so unfettered, so unrestrained that every single one of his 29 subsequent studio albums has something irresistible within its grooves.

Of course, they did try to restrain him. They invented Parental Advisory stickers to tame his libidinous lyrics. The tabloids seized upon his height, his clothes and his lothario tendencies and attempted to turn him into a figure of fun as they had with his peer/rival Michael Jackson. But, unlike with Wacko Jacko, they never made it stick – Prince was simply too multi-faceted an artist to be boiled down to a single, defining characteristic.

Ultimately, the only time he came close to being undone was by his own hand. While he undoubtedly had a good point to make about respecting the power of the artist, his fallout with Warner Music in the ‘90s, just as the gathering forces of grunge and Britpop threatened the empire of the great ‘80s superstars, forced his hand into profligacy. He churned out albums in an attempt to free himself from his contract and turned up to the 1995 BRITs with ‘Slave’ daubed on his cheek (just one of his many memorable appearances at the UK’s premiere music awards ceremony).

Your correspondent had the pleasure of interviewing around that time, as Prince embarked on a string of Wembley Arena gigs that reminded the nation that, even if his albums had become a bit hit and miss, his live shows were still far more of the former than the latter.

Interviewing him proved every bit as unusual as you’d hope. No tape recorder or notebook was allowed, the interview took place in almost total darkness in a candlelit, incense-scented dressing room swathed in purple and turquoise. This being for Smash Hits, I mainly asked him daft questions about whether he’d snogged Kylie Minogue or how you were supposed to pronounce the symbol he had changed his name to at the time.

He indulged those queries, but always adroitly turned the conversation back to what he wanted to say, and it’s those quotes that have stayed with me. Firstly, he said that the major label system was on the way out and that, one day, in order to get his music, all you’d have to do is “give me your address and I’ll send you my album on the internet”. At the time, most people hadn’t heard of the Internet, let alone Amazon.

That set the tone for the way Prince operated for the next 20 years. He often embraced innovation, but always did things his way, whether that meant enraging retailers by releasing his albums free with the Mail or the Mirror or even annoying his own fans by attempting to purge any mention of him online that wasn’t from his official outlets.

But, ultimately, it was that cussedness and belief in his own worth that kept Prince in the limelight when his contemporaries faded away. Take a look at that other diminutive controversy-magnet, Eminem and his 2002 single Without Me for proof, where Slim Shady declares he’s been “suspenseful with a pencil, ever since Prince turned himself into a symbol”.

The other namedrops on that single were utterly contemporary – NSYNC, Moby, Limp Bizkit – with Prince and Elvis the only veterans worthy of a mention. Fourteen years on, they’ve all faded from view and yet Prince, courtesy of his 2007 O2 residency and his 2014 guerrilla gigs was probably as revered in the UK as ever.

Your correspondent was lucky enough to catch one of those shows, at a delirious Shepherd’s Bush Empire. Fans had queued from the midday announcement to pay £10 for a ticket and it seems fair to say they got their money’s worth: the epic show ultimately cost around 25p per song, although he was as likely to reduce The Most Beautiful Girl In The World (even more unfathomably, his only UK No. 1 single) to a single line as he was to elongate 1999 album track Something In The Water (Does Not Compute) into a 10-minute blues-funk jam.

But such moments were always underpinned by such breathtaking, incendiary musicianship that they never felt over-indulgent. It put me in mind of one of the other things he said to me back in Wembley in 1995.

“I guess my life might seem strange to some people, but it’s normal to me,” he smiled. “I don’t really have much of a life outside of music. I don’t eat breakfast. In fact, I hardly eat at all, I don’t like it very much. I don’t sleep either. I just stay up all night playing music.”

Now, tragically, there will be no more late night jams at Paisley Park, although you can bet that the music he created there – and we have by all accounts only heard a fraction of it to date – will be soundtracking all-night parties and early morning contemplations for generations to come.

Because whether you’re rich or poor, cool or uncool, when it comes to getting through this thing called life, Prince Rogers Nelson will always rule your world.